Stanton, NJ History: How Christian Harshall and the Housel Family Shaped Hunterdon County

According to Hunterdon County, N.J. historian Stephanie Stevens,

“Tucked into the southwest corner of Readington, the Stanton Village extended to its western boundary line and began to take up lands in the 1740s along the highway. Their plantations created the community, which was originally named Housel, after one of them. A property line between farms became the basis for a north-flowing road, Mountain Road today, that led to interior settlements earlier established by an overflow of the Dutch of Somerset County on the east.” [1]

The area now known as Stanton became pivotal in the 18th century as part of an expanding rural settlement anchored by Dutch and German immigrants. Their contributions are thoroughly documented in the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (NRHP), which highlights the critical role of families like the Houssels and Harshalls in shaping the region's development. The NRHP describes Stanton’s transformation from isolated plantations to an interconnected village supported by critical transportation routes like Mountain Road and King’s Road. These roads not only facilitated commerce but also served as a lifeline for early settlers, linking Stanton to mills, markets, and other key locations. Later in the document (a registration form attempting to qualify Stanton as a Historic Rural District in the National Register of Historic Places), Stevens continues,

”Housel’s dwelling and farm, in clear view on the main road, became the name the neighborhood was known by. Both Robert Erskine (1778-1783) and Lt. John Hills (1781)[2] included it on their military maps. Mills on the South Branch at nearby Prescott Brook in Clinton Township were described in the eighteenth century as being situated along the "‘road to "Housels.’”[3]

The NRHP underscores the foundational role of Johannes Christian Harshall (later anglicized to Housel) in shaping Stanton's identity. His documented 1731 purchase of 150 acres from Daniel Coxe positions him as one of the area’s earliest settlers. This acquisition, combined with his later landholdings, cemented Harshall’s position as a key figure in Stanton’s early development and agricultural economy. The name "Housel's," central to the area's development, reflects both the German roots of the Harshall family and the prominence of their farmstead on the early maps of the region. This early acquisition, along with Harshall’s subsequent partnerships in larger land purchases, cements his foundational role in Stanton’s emergence as a community.

“Following the death of Col. Cox's son John Cox in 1755, the estate administrators issued a deed to William Housel for 146 acres lying along the south side of the highway and backing on Round Mountain, for land already in his possession, apparently honoring an understanding made with him.”[4]

The Housel-Wagoner home, as described in the NRHP, exemplifies a "vernacular deep-form bank house" with architectural features that reflect the German and Dutch heritage of Stanton's early settlers. While the property came to be associated with Rev. William Housel, its construction—dated as early as 1741—likely points to earlier settlers such as Christian Harshall or other prominent German landowners in the area. Its stone construction and integration with the sloping terrain are characteristic of early German settlement patterns in Hunterdon County. The establishment of the Housel farm along King’s Road not only provided sustenance for the settlers but also helped shape the emerging local economy. As the NRHP highlights, the proximity to mills and other infrastructure along the South Branch of the Raritan River played a crucial role in the area's growth.

“A Sketch of the Northern Parts of New Jersey.” By. Lt. John HillChristian Harshall’s role as a foundational figure in Stanton is further demonstrated through his integration into the social and religious fabric of the community. Harshall’s appearance at the 1729 baptism of Johannes Hoffman’s daughter at the Reformed Dutch Church of New York shows an early association with other prominent settlers. Harshall’s first wife, Eleanor Rudig, was connected to the Dunker religious community, which prioritized simplicity and service—values reflected in Harshall’s contributions to Stanton’s early development. These connections highlight his influence within the tightly knit German-Dutch settlement.

The intersection of Harshall’s German heritage and the English settlement patterns of Hunterdon County offers a window into the blending of cultural traditions and architectural styles that shaped this early American community. Attempts to identify the founder of the Housel’s farming community have whittled themselves down to three. We will attempt to tackle them all.

Theory One: Jacob Housel (Abt 1700 - Aft 4 Apr 1761)

Claim: “An early settler at present Stanton was one Jacob Housel. The locality was originally named after him, ‘Housel's.’ By the early 19th Century, the Housel home (now the home of Mrs. George Brightenback) had come into possession of William Waggoner and the place name became ‘Waggoner's’ or ‘Waggoner's Hill’.”[5] This narrative, while compelling, appears to derive from secondary sources such as Franklin Ellis’s 1881 book, History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey, which often provides anecdotal claims without substantiating them with primary documentation.

Claim: “A fine example of a German Bank house is the old Jacob Housel house in Stanton built 1738-40. It is on the south side of the road leading to the foot of Housel’s or Round Mountain” (John Smith Descendants, 289)[6]

Probability (low): The claim that Jacob Housel was Stanton’s founder lacks primary evidence, especially when compared to the well-documented land transactions of Christian Harshall. Unlike Harshall, whose 1731 deed from Daniel Coxe is supported by both original records and geographic alignment with Stanton, Jacob Housel’s activities remain centered in Amwell Township near Ringoes. For instance, Jacob’s 1761 will confirms his residence in Amwell, where he purchased land from Andrew Trimmer. This geographic discrepancy and lack of Stanton-specific documentation weaken the case for Jacob’s involvement in the founding of Stanton. Furthermore, that Jacob was the Housel community’s namesake seems unlikely for the following reasons:

Jacob’s brother, John, “purchased land along the Old York Road south of Ringoes from Joseph Arney in 1729 (O (WJ): Folio 197 (SSTSE023)), making him one of the original inhabitants of the Nathan Allen tract in and around Ringoes (an Obadiah Howsell is also mentioned).[7] This establishes the brothers' presence firmly in Ringoes, with no documented ties to Stanton.

John’s will states that he still lived on the plantation in Amwell that he purchased from his father-in-law, Andrew Trimmer, at the time of his death.[8]

Jacob and John were listed as Freeholders in Amwell Township in 1741 (the same year the Howsel-Wagoner house in Stanton was erected ).[9]

Jacob’s other brother, Matthias, in 1767 was an Elder in the German Reformed Church in Amwell (later Presbyterian).[10]

The 1761 will of Jacob Houshal indicates that he was still a resident of Amwell who had bought land from Andrew Trimmer, John Housel’s son-in-law.[11]

Although the men baptized their children at nearby Readington Reformed and Dutch Reformed churches (6-10 miles from Housel’s), both men lived, died, and were buried near Ringoes. This religious connection to nearby churches does not provide sufficient evidence of residency or leadership in the Stanton farming community.

None of these signs point to either of these men being the founders of a farming community near present-day Stanton. The existing documentation ties them more closely to the Amwell area, further reducing the likelihood of Jacob or John establishing Stanton.

Counter-Theory: An Unknown Jacob Housel Sr.Unless there existed an unknown Jacob Housel, Sr., potentially predating documented records and connecting directly to Christian Harshall or Rev. William Housel, the lack of concrete evidence surrounding Jacob Housel’s presence in Stanton precludes him from being definitively named as the community’s founder. The weight of available documentation points instead to Christian Harshall as the key figure establishing the Housel name in Stanton. The existence of such a figure would need to be supported by lost deeds, probate records, or mentions in early Hunterdon County land leases, none of which have yet surfaced in the historical record.

Theory Two: Johannes “Christian” Housel (Abt 1700 - 1769)

Claim: David Leer Ringo, author of “The Millennium Library Edition of the Ringo Family History Series,” offers his own theory which currently holds sway on Wikipedia .[12] Ringo asserts the area was named Housel’s after Johannes Housel, “who had a farmstead along Dreahook Road in the mid-18th Century.” However, Ringo’s theory does not identify who Johannes Housel was or provide concrete evidence tying him to the land. This ambiguity leaves room to explore whether Johannes Housel and Christian Harshall could, in fact, be the same person.

Probability (high): The application for historic status confirms Christian Harshall’s prominent role in Stanton’s development. In 1731, Harshall acquired 150 acres from Daniel Coxe for £150, a tract described as “bounded southwesterly by Campbell’s Brook, westerly by Andries Redrick’s land, northerly by the late Thomas Bowman’s estate, and southeasterly by Cornelius Bowman’s estate.” This land formed the nucleus of what would become Stanton, anchoring early settlement patterns along critical transportation routes like King’s Road and Mountain Road. In 1752, Harshall further solidified his influence by partnering with Peter Yager, Andries Rederick, and Johannes Schmidt to purchase 447 acres from the Cox heirs, demonstrating his integral role in the area’s expansion.[13].

In August of 1765, Christian Harshall formalized his lasting influence on Stanton through his will and four deeds transferring 274.5 acres of his land to his son-in-law, John Henry Smith. These deeds not only preserved Harshall’s family’s presence in Stanton but also reflect his strategic role in shaping the community’s geography and economy. One deed states the land is “bounded by Campbell’s Brook and the estates of Andries Redrick and Cornelius Bowman,” situating Harshall’s holdings at the heart of Stanton. The transfer ensured that his land, first purchased in 1731, remained central to the area’s growth and legacy.

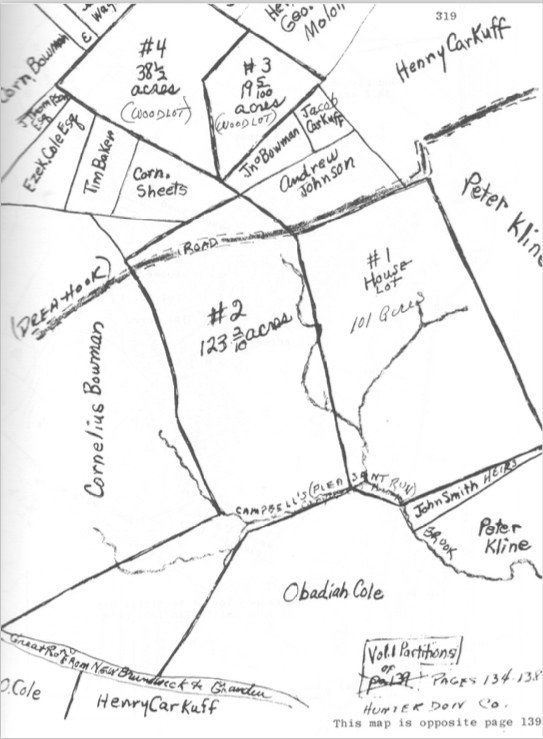

The first deed from Christian to John indicates that his land is “bounded southwesterly by Campbell's Brook, westerly by Andries Redick's land, northerly by lands of the late Thomas Bowman, and southwesterly by land of Cornelius Bowman.” It was initially purchased for 150 pounds for 150 acres by a deed dated November 13, 1731.[14] We can see clearly on a partition map of properties in John Smith Descendants by Beverly B. and William Francis Smith that the lands of John Henry Smith “were a farmstead on Dreahook Road in the mid-18th Century.” As John Henry inherited them from John Christian Harshall, who owned them as early as 1731, this establishes Johan Christian Harshall as the probable identity of Johannes Housel in David Leer Ringo’s theory. This conclusion aligns with Christian's established presence in the community and his historical documentation as an early landholder.

Not only had Christian owned land there since 1731, but his friend, John Hoffman (whose daughter’s baptism he had attended in 1729) also lived on a plantation purchased from the Cox heirs, where he lived until his death in 1741.[15] This connection to Hoffman adds weight to Christian's integration into the local landowning class and strengthens the case for his central role in the area's development.

Land of John Henry Smith (1718-1791) inherited from father-in-law John Christian Harshall. Dreahook Road is visible to the north.

Theory Three: William Housel (1726-1809)

Claim: According to “Pre-Revolutionary Dutch Houses And Families In Northern New Jersey And Southern New York” by Rosalie Fellows Bailey, “There is an old stone barn, dated 1741, and the house may have been erected at the same time.[16] The property was owned during the Revolution by William Howzel, a member of a German family which had settled in this vicinity before 1735.”[17][18] This supports the theory that the Housel name was established in the area before 1735, potentially validating the claim that Christian Harshall played a foundational role in the community.

The Relationship Between Rev. William Housel and Christian Harshall: Rev. William Housel, possibly the son of Christian Harshall, provides an intriguing case study of Stanton's early religious and social dynamics. While Christian’s 1765 will does not name William, the omission aligns with 18th-century practices of excluding children who had already been provided for or who pursued independent lives. Rev. William’s proximity to Christian’s land, his documented association with the Housel name, and his role as executor for Anthony Harshall’s estate lend strong circumstantial support to this familial relationship. This connection also explains Rev. William’s deep ties to Stanton’s spiritual and educational legacy. Despite not being named in Christian’s will, several factors strengthen this possibility:

Precedent of Exclusion: As seen in other 18th-century wills, exclusion of children—especially those who were already provided for or who rejected material wealth—was not uncommon. Christian’s omission of Rev. William Housel could reflect similar dynamics. For instance, Christian’s will divides property and resources among named heirs but does not allocate anything to his grandson Marten, despite other grandchildren receiving substantial bequests. This precedent underscores that omission does not necessarily equate to disinheritance.

Spiritual Priorities: Rev. William Housel was deeply committed to his ministry and charity work, leaving his earthly possessions to benefit the poor rather than his kin. This aligns with the values of Christian Harshall’s first wife, Eleanor Rudig, who was connected to the Dunkers—a sect that prioritized simplicity and service over material wealth. Rev. Housel’s lifestyle likely diverged from his father’s increasing material ambitions, potentially creating a divide.

Name Evolution: The adaptation of "Harshall" to "Housel" reflects both phonetic anglicization and practical adjustments to avoid anti-German sentiment during and after the Revolution. This evolution mirrors broader trends in the Harshall family, who also adopted variations like "Herschild" and "Hessel." Rev. Housel’s surname choice may have been influenced by his desire to distinguish himself from Christian’s wealth-driven legacy.

Circumstantial Evidence: Rev. Housel lived on land adjoining Christian’s property, and the timing of his acquisition coincides with Christian’s subdivision of his holdings. The proximity of their lands and the interconnectedness of their social networks (e.g., shared associations with Hoffman, Rudig, and Yager families) suggest a familial relationship. Additionally, William’s appointment as executor for Anthony Harshall’s estate supports his close connection to the Harshall family (as Anthony was likely William’s brother).

Conclusion: While the will does not explicitly confirm Rev. William Housel’s parentage, the circumstantial evidence points strongly to his relationship with Christian Harshall. William’s presence in Stanton—on property likely facilitated by Christian—sustains the Housel name’s prominence in the region, even if his personal values diverged from his father’s.

Claim: “A village has existed at the base of Round Mountain since the first Dutch settlers came to the area in the 17th century, attracted by the beautiful countryside and farmland. The village was first called Mount Pleasant, later Housel’s, and then Waggoner’s Hill.[19] Finally, the name was changed to Stanton in 1849…”[20] A school was established in Stanton in 1780 when a small building on a triangular plot of ground was erected in the forest. When [Rev.] William Housel died 20 years later, he left $200 to be applied to the poor children of the neighborhood. The school was then known as Housel’s Free School…Dreahook comes from the Dutch word for triangle. It was possibly named for the convergence of the roads to Whitehouse, Flemington, Readington, and Pleasant Run, where the families of Wyckoff, Voorhees, Van Devanter, Kline, Krug, Emery and others settled to farm the rich soil near Round Mountain. The hamlet boasted a blacksmith shop, a school and a store.”[21]

Claim: A 1781 map containing part of the Provinces of New York and New Jersey by Andrew Skinner (below) clearly shows the Housel farm on the south side of Kings Road (now Stanton Road), where Rev. William Housel lived in the Howsel-Wagoner home.[22]

The continuity of Housel occupancy in Stanton, from Christian Harshall’s initial land purchases in 1731 through Rev. William Housel’s later stewardship, underscores Harshall’s pivotal role in shaping the community. Harshall’s documented landholdings, strategic partnerships, and enduring legacy through the Housel-Wagoner property firmly establish him as the founder of Stanton. This narrative not only strengthens his historical significance but also highlights the blending of German heritage and American frontier traditions in early Hunterdon County. But who built the famed Howsel-Wagoner home?

Here are some facts about Rev. William Howzel (not to be confused with William D. Houshell):

Rev. William Howzel, according to his tombstone,[23] was born in Neuwied[24]in 1726.

According to church history, we know that he accepted a call to the ministry of the Amwell Church of the Brethren (aka. German Baptist Church in Amwell Twp.) about 1950.[25]

This church was comprised of many former residents of Neuwied.

William married Altia Newell sometime before her father’s will was written in 1762.[26]

The couple died childless and left nothing to any Housel heirs. They donated money to support the church’s poor and educate the children of Housel’s.

William and Altia donated their farm that bordered John Smith’s “Wood Lot-#4” (see partition map above) to Jacob Waggoner, Sr. This donation likely contributed to the property being renamed “Waggoner’s.”

The house in which William Howsel lived was located less than 2 miles from a bank home allegedly built by his neighbor, John Henry Smith, in 1750[27] but more likely by his father-in-law, Christian Harshall.[28]

William Howsel’s parents have not been identified even by the most thorough of New Jersey researchers like Mary Goodspeed.[29] However, Andreas Rudig, Peter Yager, and Christian Harshall—each born before 1700—were old enough to have been Rev. Howsel’s father. Of these men, only Christian’s last name is homophonic with Housel, suggesting a plausible familial connection.

Rosalie Fellows Bailey states that the old stone barn on the property was dated 1741, and the house may have been erected simultaneously. Given that William Housel would have been only 15 years old in 1741, it is unlikely that he had the carpentry and masonry skills necessary to build a home and barn, nor the immediate need for such structures at that age.

Probability (mostly true): It is likely that Rev. William Housel lived and occupied the Howsel-Wagoner home, possibly from childhood. His presence and philanthropic work in the community kept the Housel name alive until after his death. At that point, the property became associated with Jacob Waggoner, and the nickname “Waggoner’s” emerged. However, whoever built the Howsel-Wagoner home and lived in the area prior to 1735 is likely the true source of the name “Housel’s.” This reinforces the idea that William, while important in maintaining the name and legacy, was not the original founder of Housel’s but may have inherited and preserved its significance.

We can now narrow our search to at least two Housel men in the vicinity before 1735 who may qualify for the title.

Gasper Hewskill[30] (aka. Kasper/Casper Hauschildt, abt.1675-1739)

Casper Housel emigrated in 1735, according to Henry Z. Jones.[31]

In 1735, Lewis Morris, Jr. made a list of 96 families who settled on the 12,535 acres of the West Jersey Society’s Great Tract (besides those on the part claimed by Coxe and Kirkbrides). Casper was listed among them, having leased 150 acres.[32]

Hypothesis: Casper is believed to be the father of Johannes Houshell, Jacob Housel, and Matthias Houshill of Amwell Township.

Jacob Housel may correspond to the Jacob referenced in Theory One, as both are tied to early records in the Amwell area.

Family historians have noted numerous variations of the Amwell Housel surname, likely reflecting phonetic “anglicizations” based on transcribers’ unfamiliarity with German names. These variations include:

Johan Chrystean Hessel (aka John “Christian” Harshall, abt. 1700-1769)

Evidence: In 1731, Christian purchased land on the Coxe and Kirkbride tract, suggesting his arrival in the area predates this purchase.

Christian Harshall’s name has appeared in historical documents as:[47]

Harshal

Harsell

Hassel

Hessel[48]

Hasell

Hersel

Haskel

Hasskel[49]

Analysis: The evolution of "Hauschildt" into both "Housel" and "Hessel" seems plausible given the linguistic challenges of transcribing non-English names. Imagine a first-generation Dutch or German immigrant pronouncing "Hauschildt," and a scribe writing it down phonetically based on their perception.

Additional context:

Johan “Christian” Harshall seems to arrive on the scene at roughly the same time as Casper and his family of Housels, although we find an obscure reference to a “Howsel west [of Ringoes] in 1725.”[52] Evidence from Harshall’s naturalization record suggests he may have been in the area as early as 1723, which would qualify him as a plausible candidate for the “Howsel west [of Ringoes]” referenced two years later. Christian first appears in Long Island, recorded as Christiann Hessel, when he witnessed the baptism of Catharina, daughter of Johannes Hofman and Margriet Anhuys at the Reformed Dutch Church of New York on January 26th, 1729. This connection to the Hoffman family situates Christian within the early Knickerbocker network before his move to New Jersey.

Records from 1677/78 in Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany, document a Jacob Hessel, potentially linked to the Harshall/Housel family that later established itself in Stanton. This evidence suggests a transatlantic continuity of the Hessel/Harshall lineage, with the German name “Hessel” aligning closely with early mentions of Christian Harshall as "Christiann Hessel" in New York. As noted in The Early Germans of New Jersey by Theodore Frelinghuysen Chambers, this connection reinforces the likelihood of a shared family origin, spanning Germany, New York, and New Jersey.

The Hoffmans

John Hoffman was well connected within the Knickerbocker community in New York and had numerous relatives there. He descended from an illustrious line of Swedish-German Hoffmans who married the nobility of Holland.[53] This lineage not only brought prestige but also significant wealth after emigrating to America.[54] John’s granduncle, Martinus Hoffman, was Ritmaster of the Lutheran King, Gustave Adolphus[55] before emigrating to New York.[56][57] King Adolphus planted a Swedish colony on the Delaware, where Germans later sought refuge from the Thirty Years’ War.[58] Among Martinus’s “descendants were Governor of New York John T. Hoffman, Congressman Ogden Hoffman, New York Attorney General Josiah Ogden Hoffman, State Senator Anthony Hoffman, several clergymen of the Dutch Reformed Church, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.”[59]

Martinus’s brother, Ludwig, was John Hoffman’s grandfather. Ludwig’s son, Hendrix Hoffman, had at least three boys.[60] William emigrated to New Jersey as a child and was the g-g-grandfather of Governor Harold G. Hoffman of New Jersey.[61] John Peter emigrated to Philadelphia and remained in Pennsylvania.[62] Our John Hoffman, who befriended Christian Harshall, moved from New York to a New Jersey plantation where he lived until his death in 1741.

John and Margaret Hoffman had six children who intermarried with families that figure prominently in the Smith family line, including the Cole, Bellis, Wyckoff, and Bowman.[63] A partition map in John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants shows the lands of Cornelius Bowman and the Cole family abutting Christian Harshall’s.[64]

The Amwell Brethren

Christian was naturalized on July 8th, 1730, alongside his brother-in-law, Johannes Peter Yager, Anthony Dirdorf[65] (and his four sons, Peter, John, Anthony,[66] and Christian) and Matteys Smith (who we shall discuss later).[67] The name immediately following Christian Hasell’s on the naturalization list is Johan Housilt of Amwell, suggesting a possible connection or familiarity.[68] Also listed is John Housel’s brother, Jacob. Because the naturalization process required at least seven years of continuous residence, Dr. Ken Stryker-Rodda places these men’s arrival about or by 1723, which may explain the 1725, “Howsel west of Ringoes,” reference to above.[69]

At the 1730 naturalization, six men–Johan Peter Rockefelter, Jacob Sartor, Johan William Berg, Martin Fisher, Johannes Giddeman, and Anthony Dirdorf–are listed with the phrase “and his ‘x’ number of’ sons” after their name. The fact that Jacob, John, and Christian are individually named, without being identified as sons of any of these men, is significant. It suggests that Christian Harshall was likely not the father of Jacob and John, effectively ruling out that relationship.

Unraveling the Housel’s mystery may lie in investigating the consortium of family, friends, and real estate partners who were naturalized with Christian on that day. Anthony Dierdorf, a neighbor of Christian Harshall in Stanton,[70] was likely part of this network. Like many in Christian’s circle, Anthony probably hailed from the Duchy of Neuwied,[71] an attractive town with a population of about ten thousand, comprising Romanists, Lutherans, Moravian Brethren, Baptists, and Jews who coexisted peacefully.[72] Neuwied was a haven for those fleeing religious persecution. “In 1705, a number of German Reformed people from Wolfenbüttel and Halberstadt, driven by persecution, fled first to Neuwied in Rhenish Prussia, and then to Holland.” [73]

Anthony was a follower of Alexander Mack and a member of the Church of the Brethren.[74] This Pietist sect included many who had left the Reformed Church and fled the German Rhine Valley to Switzerland and Holland to escape persecution.[75] According to the History of the Brethren Church of the Southern District of Pennsylvania, Anthony Deardorff, along with Jacob More, John Nass, Rudolf Harley, and John Peter Laushe, helped establish the second Brethren Church of this denomination in America in 1733 at Amwell, N.J.[76][77] They split from their brethren in Germantown, PA, after a controversy involving a Brethren man marrying a Mennonite woman.[78][79] Additionally, a branch of the Ephrata community, a famed offshoot of the Brethren, existed in Amwell as late as 1738.[80]

“The group left Philadelphia and found their way north into Amwell Township, taking the “Old York Road” from Pennsylvania into New Jersey. They congregated at Ringoes, an early mill and merchant settlement, with Germans appearing in such numbers that as early as 1721, the near vicinity was referred to as ‘the Palatins’ Land.’”[81] The Amwell Church of the Brethren was located about a mile from Sergeantsville, west of Ringoes.[82]

However, the Amwell Housels seem to have been more closely tied to the German Reformed people “driven by persecution…to Neuwied,” rather than the Brethren. Evidence for this connection includes Anthony Dierdorf’s donation of land to establish a new German Reformed Church in 1749. Matthias Housel, listed as an elder of this church, suggests that the Housels were part of this congregation.[83] Many members of the Housel family are buried nearby.[84]

Christian’s brother-in-law, Peter Yager was cited on a list of Brethren church members by Alexander Mack, Jr. sometime before 1803.[85] Peter’s daughter, Anna Maria, continued in the Brethren faith, marrying Anthony Dierdorff, Jr., an officer in the church.[86] Christian Harshall and Peter Yager both married daughters of Andreas Rudig—Eleanor and Catherine, respectively. Andreas Rudig was naturalized on August 20, 1755, as one of a group of German Anabaptists permitted to affirm their allegiance rather than take an oath, a key practice of their faith.[87]

A long-lost son? A prodigal father?

Rev. William Howsel (1726-1809) provides a lens to examine the dynamics of the Housel’s community. While little is known about his early life, it is possible William operated, like many farmers of the area, under a lease agreement made during the 1740s. However, at that time, he would have been very young—perhaps raising questions about his family connections and how he came into such arrangements. In 1755, the estate of John Cox issued a deed to a twenty-seven-year-old Rev. Howsel for 146 acres along the south side of the highway and backing Round Mountain.[88]

Four years earlier, in 1751, Christian Harshall, Andreas Rudig,[89][90] Peter Yager,[91] and Johannes Henry Smith purchased 447 acres from the children of Daniel Cox[92] and proceeded to subdivide the land four months later. Rev. Howzel’s land may have been part of this subdivision. Interestingly, Christian’s tract lay just across the highway to the north, directly adjoining Rev. Howsel’s property.[93] This proximity raises the possibility that the deed granted to Rev. Howsel was not merely a transaction, but part of a familial or community arrangement orchestrated by Christian Harshall to benefit William Housel. This brings us to the next question: “Why?”

The family and parentage of Rev. William Howsel remain unknown to history, but we know Christian Harshall was old enough to be William’s father. Moreover, the frequent use of the name William among the descendants of Christian Harshall may suggest a family connection. The men were acquainted, lived as neighbors, and likely collaborated as farmers. For instance, in 1788, William Housel oversaw the inventory of Anthony Harshall’s (Christian’s son) estate.[94] Both William and Anthony Harshall used variations of the Harshall name, such as Housel and Herschild, in their documents.

This evidence invites us to ask: “Is it possible that Rev. William Howsel was the son of Christian and his wife Eleanor Rudig?” If this theory holds, several puzzling inconsistencies remain to be addressed:

Why is William not mentioned in Christian Harshall’s will?

Why did Rev. Howsel refuse to leave any property or wealth to his Housel kin, including many in Amwell, where he preached?

Why did Rev. Howsel use a different spelling for his surname, diverging from Christian’s spelling of Harshall?

Was the Howsel-Wagoner property a wedding gift, potentially arranged by Christian for William?

Christian’s first wife, Eleanor Rudig, died in her thirties. By 1741, when his friend John Hoffman died, Christian was referenced in his will as Hoffman’s brother-in-law. This familial connection was intriguing but vague. Christian’s second wife, Elizabeth, is mentioned in his will, and she appears to have previously married a Hoffman, with whom she had a child named Mary (born 26 July 1729). Mary later married John Smith, son of Matteys, in May 1748. However, the exact relationship between Elizabeth and John Hoffman remains unclear, as there is no known sister of John Hoffman named Elizabeth, nor are there documented brothers. What is clear is that the religious beliefs of Eleanor Rudig and Elizabeth Hoffman were drastically different.

Dunkers attempted to live as close as they could to the practices of primitive Christians. They dressed in plain clothing, similar to their “cousins,” the Amish and Mennonites. They refused to take oaths (as evidenced by Andreas Rudig), practiced pacifism, banned slavery, and viewed lending money at interest as the sin of usury (money could be given freely and repaid but not at interest). Eleanor Rudig, as part of this community, likely instilled these values in her children. Whether William was the son of Christian and Eleanor or not, he grew up adjacent to Dunker families who practiced this faith, and he later adopted these values as a leader of the Dunker community.

It becomes evident that whatever Christian Harshall’s beliefs were while married to Eleanor, after her death, he seemingly abandoned these principles in favor of the Hoffman family’s less idealistic Christianity. Whether motivated by nobility, enterprise, or ingenuity, Christian became one of the wealthier Germans in Hunterdon County, storing up for himself and his descendants substantial earthly treasures. According to records held by subsequent owners of his property, Christian at one time owned 1,200 acres, including a carriage house, stone smokehouse, a large barn, and other small buildings.[95] At the time of his will’s execution in 1765, Christian had £1,281.11.0 out at interest (equivalent to over $270,000 in 2022 dollars[96]).[97] This wealth and lifestyle were a significant departure from the Dunker values he may have once held.

Christian openly diverged from many of the Brethren’s core beliefs. He swore an oath of allegiance—a practice rejected by Dunkers—and many of his descendants later joined fraternal and secret societies that required such oaths. He owned slaves, naming them in his will. Before his death, he lent over £100 each to Elizabeth’s sons-in-law, John and Jacob Smith, securing mortgages on their land in Amwell, formerly owned by their father, near the Amwell Housel’s Reformed Church on Copper Hill.[98] His daughter and son-in-law, John Henry Smith, who apprenticed under Christian, followed in his footsteps. John Henry became a substantial moneylender and a member of Zion Lutheran Church in Oldwick. Unlike the Dunkers, John Henry baptized his children at birth rather than waiting until they reached the age of understanding. He rejected pacifism and fought in the Revolution alongside his son Martin at Millstone Village.[99] Martin also owned slaves[100].

One can imagine a young Rev. William Howsel, called to the ministry, observing Christian’s apparent rejection of the Dunker faith Eleanor Rudig may have instilled in their household. To an idealistic man in his thirties, committed to pastoral work, this shift might have symbolized a capitulation to materialism and earthly ambition. If researchers could verify that the Howsel-Wagoner home was deeded to Rev. Howsel as part of his marriage to Altia Newell, it might support the theory of a wedding gift and further illuminate family dynamics. According to The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies, William remained farming in Stanton until around the time of Christian’s death[101] after which he accepted a position in Amwell pastoring the Dunker church, which had only 28 families and approximately 140 members, many of whom had ties to Christian Harshall.[102] Rev. Howsel’s commitment to his faith is underscored by his actions at the time of his death: donating his possessions to the poor in the community and establishing a school for underprivileged children in Housel’s.

While this evidence does not conclusively prove that Rev. William Howsel was the son of Christian Harshall, it provides compelling circumstantial evidence and offers possible motivations for Rev. Howsel’s choices. It also leaves room for future researchers to explore. More likely, Christian was a contemporary of Jacob and John Housel, possibly their cousin. What we do know is that the Herschild/Harshall branch of the family resided in present-day Stanton, while the Hauschildt/Housel branch was centered in Amwell Township. The two families likely share a common origin and a recent ancestor from the time of emigration, a theory that DNA testing could potentially validate.

Conclusions:

Christian Harshall is the earliest known “Housel” to reside in Stanton, having arrived as late as 1731 but as early as 1723.

His land, acquired from the Cox and Kirkbride tract, was later subdivided, and one of its boundaries aligned with the Howsel-Wagoner home and property. This proximity reinforces Christian’s direct connection to the area that bore the Housel name.

Historians agree that whoever built and lived in the Howsel-Wagoner home was the individual after whom Housel’s was named.

Christian may have initially leased or controlled the Howsel-Wagoner plantation lands and facilitated their eventual sale directly to William Housel.

Christian is a plausible candidate for having owned, built, and lived in the Howsel-Wagoner home before Rev. William Housel, given his wealth and presence in the area by the 1730s.

William was too young to have built the house by 1741, when the stone barn on the property was dated.

Christian’s reliance on enslaved individuals and hired redemptioners, such as John Henry Smith or Caspar Berger, suggests they may have contributed to constructing the Howsel-Wagoner home or other properties Christian owned.

Christian built and occupied another bandbox home on the adjoining property, which still exists today. He gave that property to his son, John Henry Smith, before his death in 1769.

Edith Tiger Canfield, a John Henry Smith descendant, used to recite an old rhyme to her nephew George Tiger when he’d start digging into their family history, “Johns and Jacobs, Jacobs and Johns, leave it alone before you find a skeleton.”[103]

Addendum:

For those possessing knowledge of such things, a review of the photographs and links below with an examination of the extant literature regarding the two existing Howzel/Housel properties in Stanton may highlight similarities and differences that may shed further light on the home’s builders.

The Howsel-Wagoner property (right)

Write-up of characteristics here (section 7, page 8)

The Christian Harshall/John Henry Smith home (left)

Footnotes:

[1] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, July 13, 1990. NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. National Parks Service. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/47df132f-67e7-494a-a0c8-a3a00b5fdab6.

[2] Hill spells it Hozells on his map.

[3] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” Section 8, Page 4.

[4] Ibid. Section 8, Page 2.

[5] Hunterdon Historical Newsletter. “Place Names...Stanton,” Spring 1966. 6. https://hunterdonhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Newsletter-Spring-1966.pdf

[6] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ?

[7] New Jersey Historical Society. Proceedings. Newark, N.J, 1845. 73. http://archive.org/details/2nd5t8proceedings05newjuoft.

[8] We Relate. “WILL and Inventory of Johannes Houshill (1698-1761).” Forum, 2007. https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Image:JHH-WILL-2pg.jpg.

[9] Wittwer, Norman C. “Hunterdon County Freeholders, 1741.” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, May 1962.

[10] Converse, Charles S. History of the United First Presbyterian Church of Amwell, N.J. Accessed June 3, 2022. 29. www.familysearch.org/library/books/idurl/1/789099.

[11] We Relate. “WILL and Inventory of Jacob Houshall (1761) - Genealogy.” Forum, 2007. https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Source:WILL_and_Inventory_of_Jacob_Houshall_%281761%29

[12] “Stanton, New Jersey.” In Wikipedia, October 26, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Stanton,_New_Jersey&oldid=1051986368.

[13] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” Section 8, Page 2.

[14] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. 306. https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ?

[15] New Jersey Historical Society. Calendar of New Jersey Wills, Administrations, Etc. Newark, N.J, 1730. https://archive.org/details/calendarnewjers00edgoog/page/240/mode/2up.

[16] https://goo.gl/maps/Kp51AJEbsvjnewYq7

[17] Rosalie Fellows Bailey. Pre Revolutionary Dutch Houses And Families In Northern New Jersey And Southern New York Rosalie Fellows Bailey, 1936, 568. https://archive.org/details/pre-revolutionary-dutch-houses-nj-southern-ny/page/567

[18] Readington Township Historic Preservation Commission and Readington Township Museum Committee,. Images of America: Readington Township. Arcadia Publishing, 2008. 68. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Readington_Township/hdUoRow9dfwC?

[19] The Waggoners were also members of the Dunkard/Brethren faith. See: Snell, James P., and Franklin Ellis. History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia, Everts & Peck, 1881.352. https://archive.org/details/cu31924104752518/page/352

[20] Ellis, Franklin. History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Everts & Peck, 1881. https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Hunterdon_and_Somerset_Counti/AdMwAQAAMAAJ?

[21] Readington Township Historic Preservation Commission and Readington Township Museum Committee, Images of America: Readington Township. Arcadia Publishing, 2008. 61. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Readington_Township/hdUoRow9dfwC?

[22] Skinner, Andrew. “A Map Containing Part of the Provinces of New York and New Jersey,.” Image. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Accessed May 28, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3800.ar105300/?clip=2121,15310,1654,710&ciw=877&rot=0.

[23] Find a Grave. “William Housel (1726-1809).” Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13505322/william-housel.

[24] “Amwell Church of the Brethren.” Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.amwell.org/pages/about-us/95-amwell-church-of-the-brethren.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “New Jersey, U.S., Abstract of Wills, 1670-1817 -.” In Volume XXXIII, Abstracts of Wills, 1761-1770. Vol. Volume XXXIII. John L Murphy Publishing Company, April 22, 1762. New Jersey State Archives. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/13662:2793.

[27] Mackenzie, Pamela. “Banking on History.” The Courier-News. April 3, 2005, Sunday edition, sec. Real Estate. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/34793659/historic-bank-house-in-stanton-built-by/

[28] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. 306. https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ?

[29] Goodspeed, Marfy. “The Housel Family Tree.” GOODSPEED HISTORIES (blog). Accessed May 30, 2022. https://goodspeedhistories.com/the-housel-family-tree/.

[30] Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The Early Germans of New Jersey : Their History, Churches, and Genealogies. Dover, N.J. : Dover Printing Company, 1895. 635. https://archive.org/details/earlygermansofne00cham/page/n769

[31] Jones, Henry Z. “The Housel Family.” In More Palatine Families Some Immigrants to the Middle Colonies, 1717-1776, and Their European Origins, plus New Discoveries on German Families Who Arrived in Colonial New York in 1710. Universal City, California: H.Z. Jones, 1991. 124.

[32] Race, Henry. “The West Jersey Society’s Great Tract in Hunterdon County.” The Jerseyman, April 1895. http://www.usgenwebsites.org/NJHunterdon/Documents/WestJerseySociety.pdf.

[33] Deats, Hiram Edmund. The Jerseyman. [Flemington, N.J. : H.E. Deats, editor and publisher], 1891. 38. http://archive.org/details/jerseyman00deat_0. (Says Hausschild is Housel. Also, quite a number of Smith possibilities here to explore as well)

[34] Honeyman, A. Van Doren (Abraham Van Doren) and Somerset County Historical Society (N.J.). Readington Church Baptisms from 1720. Raritan, N.J. : Somerset Historical Publications, 1915. 216. https://archive.org/details/somersetcountyhi04hone_0/page/n467/

[35] Honeyman, A. Van Doren (Abraham Van Doren) and Somerset County Historical Society (N.J.). Readington Church Baptisms from 1720. Raritan, N.J. : Somerset Historical Publications, 1915. 215. https://archive.org/details/somersetcountyhi04hone_0/page/n465.

[36] From the baptism of son Johannis in 1734 to the subsequent baptism of son Pieter in 1736, the spelling of changes from to Hansel to Housel. There is also a Johannis and Neeltje Hansen that baptize daughter Elizabeth on March 28th, 1731.

[37] Honeyman, A. Van Doren (Abraham Van Doren) and Somerset County Historical Society (N.J.). Readington Church Baptisms from 1720. Raritan, N.J. : Somerset Historical Publications, 1915. 218. https://archive.org/details/somersetcountyhi04hone_0/page/n471

[38] Wittwer, Norman C. “Hunterdon County Freeholders, 1741.” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, May 1962. https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Source:Wittwer%2C_Norman_C._Hunterdon_County_Freeholders%2C_1741.

[39] Ibid.

[40] HAUSEL, Johannis. “HAUSEL, Johannis (Son of Johannis & Neeljte HAUSEL) Record of Baptism.” Dutch Reformed Church Records. Accessed May 29, 2022. https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Image:HAUSEL%2C_Johannis_%28son_of_Johannis_%26_Neeljte_HAUSEL_-_Record_of_Baptism_-.jpg

[41] East Amwell Bicentennial Committee. A History of East Amwell, 1700-1800. Flemington, N.J.: Hunterdon County Historical Society, 1979. 77. https://www.worldcat.org/title/history-of-east-amwell-1700-1800/oclc/6508258

[42] Race, Jacob. “Debt Record of Jacob Race of Amwell, Hunterdon, NJ,” 1789. We Relate. https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Source:Debt_Record_of_Jacob_Race_of_Amwell%2C_Hunterdon%2C_NJ.

[43] New Jersey, Theodore Sedgwick, Samuel Allinson, and New Jersey. Court of Chancery. Acts of the General Assembly of the Province of New-Jersey: From the Surrender of the Government to Queen Anne, On the 17th Day of April, In the Year of Our Lord 1702, to the 14th Day of January 1776. To Which Is Annexed, the Ordinance for Regulating And Establishing the Fees of the Court of Chancery of the Said Province : With Three Alphabetical Tables, And an Index. Burlington [N.J.]: Printed by Isaac Collins, Printer to the King, for the Province of New-Jersey, . 98.

[44] Houselt, Jacob. “U.S., Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States, 1639-1989.” Ancestry.com., 1744. U.S., Dutch Reformed Church Records in Selected States, 1639-1989. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6961/images/43103_356294-01004?usePUB=true&_phsrc=ICv1813&usePUBJs=true&sort=-created&pId=152535610

[45] Hunterdon Co 1733 Mortgage Register: Folio 58 (CHNLO001)

[46] “Kasper Hauschildt (Abt.1675-1739) | WikiTree FREE Family Tree.” Accessed May 29, 2022. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Hauschildt-9

[47] Harshall, John Christian. “Wills, Vol 13-14, 1766-1773.” Ancestry.com, 1765. New Jersey, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1739-1991. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8796/images/007637535_00285?pId=1317016.

[48] Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The Early Germans of New Jersey : Their History, Churches, and Genealogies. Dover, N.J. : Dover Printing Company, 1895. 406. https://archive.org/details/earlygermansofne00cham/page/406

[49] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. 315 https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ?

[50] Stryker-Rodda, Kenn. “John Christian Harshall of Readington.” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey 32, no. 3–4 (October 1957): 49–51.

[51] The adaptation of new versions of the family name came pre-Revolution for Christian. This would have paid dividends for his namesakes during the Revolution with rising anti-German sentiment directed toward Hessian soldiers hired by the British used to repress the colonists. These mercenaries, according to Andrew Mellick, were called “Dutch robbers,” “Blood-thirsty marauders,” and “Foreign mercenaries.” Given that almost half of the 30,000 German soldiers rented by Great Britain were from Hesse-Kassel, a name like Hessel could have subjected you to suspicion by your neighbors. It is noteworthy that almost 5,000 of these Hessians deserted.

[52] New Jersey Historical Society. Proceedings. Newark, N.J, 1845. 75. http://archive.org/details/2nd5t8proceedings05newjuoft

[53] Myers, William Starr. Prominent Families of New Jersey. United States: Clearfield Company, Incorporated, 2000. 8. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/qG_5K_s3a-gC?

[54] Hoffman, Max Ellis. The Hoffmans of North Carolina. M. E. Hoffman, 1938.21-24. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Hoffmans_of_North_Carolina/1PRUAAAAMAAJ?

[55] This fact from Max Ellis Hoffman needs to be researched as it appears that Adolphus died prior to Martinus’s alleged arrival in Sweden.

[56] Year Book of the Holland Society of New-York. United States: The Secretary, 1922. 191. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Year_Book_of_the_Holland_Society_of_New/0McWAAAAYAAJ?

[57] The Hoffmans of North Carolina. 21-24.

[58] Mellick, Andrew D. The Story of an Old Farm: Or, Life in New Jersey in the Eighteenth Century. Unionist-Gazette, 1889. 35. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_an_Old_Farm/mEYVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[59] “Hoffman Family.” In Wikipedia, March 7, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hoffman_family&oldid=1075796964

[60] The Hoffmans of North Carolina. 21-24.

[61] The Hoffman and Smiths stayed friendly for generations. Governor “Harry” Hoffman attended Smith family reunions in the 1930s. See: Trenton Evening Times. “Smith Descendants to Gather.” September 1, 1985, sec. A 10. https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/newspapers/image/v2%3A1236872C1F6A0AE3%40GB3NEWS-1282D04D8F8191D8%402446310-12801BF739EDF718%409-12801BF739EDF718.

[62] Kelker, Luther Reily. History of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania: With Genealogical Memoirs. United States: Higginson Book Company, 1907. 305. https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Dauphin_County_Pennsylvania/PM0wAQAAMAAJ?

[63] Bouman-Stickney Farmstead. “Skylands Visitor.” History, February 20, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200220174323/https://njskylands.com/history-bouman-stickney-farmstead

[64] Later inherited by son-in-law, John Henry Smith

[65] Egle, William Henry. Notes and Queries: Historical, Biographical, and Genealogical, Chiefly Relating to Interior Pennsylvania. Vol. Volume 1. 4. Harrisburg publishing Company, 1895. 89-90. http://wvancestry.com/ReferenceMaterial/Files/Historical_Biographical_and_Genealogical_Notes_and_Queries_for_Pennsylvania_-_Series_3_Misc.pdf.

[66] Anthony Dierdorff, Jr. married Anna Marie Yager, daughter of Johan Peter Yager. Anthony Sr. was a neighbor to Johan “Christian” Harshall, Andreas Rudig and Peter Yager. (see Stryker-Rodda)

[67] Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The Early Germans of New Jersey : Their History, Churches, and Genealogies. Dover, N.J. : Dover Printing Company, 1895. 633. https://archive.org/details/earlygermansofne00cham/page/632

[68] New Jersey, Theodore Sedgwick, Samuel Allinson, and New Jersey. Court of Chancery. Acts of the General Assembly of the Province of New-Jersey: From the Surrender of the Government to Queen Anne, On the 17th Day of April, In the Year of Our Lord 1702, to the 14th Day of January 1776. To Which Is Annexed, the Ordinance for Regulating And Establishing the Fees of the Court of Chancery of the Said Province : With Three Alphabetical Tables, And an Index. Burlington [N.J.]: Printed by Isaac Collins, Printer to the King, for the Province of New-Jersey. 98. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112203945466?urlappend=%3Bseq=112%3Bownerid=13510798902329342-116

[69] Stryker-Rodda, Kenn. “Part of Our Ancestry in the Stryker Family and Related Branches of the Harshall, Rüdig and Smith Families,” December 1959, HARSHAL (1).

[70] Ibid.

[71] Eisenberg, John Linwood. A History of the Church of the Brethren in Southern District of Pennsylvania. Quincy Orphanage Press, 1941. 410-11. http://archive.org/details/BrethrenInSouthernPennsylvania

[72] Mellick, Andrew D. The Story of an Old Farm: Or, Life in New Jersey in the Eighteenth Century. Unionist-Gazette, 1889. 36. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_an_Old_Farm/mEYVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[73] Ellis, Franklin. History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. United States: Everts & Peck, 1881. 471. https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Hunterdon_and_Somerset_Counti/AdMwAQAAMAAJ?

[74] A great history on the origins of the Brethren faith and their arrival in Amwell, N.J.: Goodspeed, Marfy. “The Amwell Church of the Brethren – GOODSPEED HISTORIES.” Accessed May 24, 2022. https://goodspeedhistories.com/the-amwell-church-of-the-brethren/

[75] Guided Bible Studies for Hungry Christians. “Church of the Brethren – Guided Bible Studies for Hungry Christians,” April 18, 2015. https://guidedbiblestudies.com/?p=2648

[76] Goodspeed, Marfy. “The German Baptist Church in Amwell – GOODSPEED HISTORIES.” Accessed May 24, 2022. https://goodspeedhistories.com/the-german-baptist-church-in-amwell

[77] Blough, Jerome E. History of the Church of the Brethren of the Western District of Pennsylvania. Elgin, Ill., Brethren Publishing House, 1916. 89-90 https://archive.org/details/historyofchurch00blou/page/34

[78] Ankrum, Freeman. Alexander Mack: The Tunker, and Descendants. Herald Press, 1943. 18. http://archive.org/details/AlexanderMackTunkerDescendants

[79] Ronald J. “Early Brethren Life in America,” February 1996. https://www.cob-net.org/america.htm

[80] Sachse, Julius Friedrich. The German Sectarians of Pennsylvania: 1742-1800. author, 1900.98.

[81] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, July 13, 1990. NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. National Parks Service. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/47df132f-67e7-494a-a0c8-a3a00b5fdab6. Section 8, Page 2. The Amwell Church of the Brethren was located about a mile from Sergeantsville, west of Ringoes.

[82] Genealogical Facts and Stories of the Dierdorff Family. p. 7.

[83] Matthias is listed as an elder in 1767. The parsonage in 1749 is near Copper Hill (where Mathias Smith and Adam Bellis lived) and the deed to the property styles the church, the “Calvenist or Priesbeterian Church in the Township of Amwell.”

[84] Deats, Hiram Edmund. Tombstone Inscriptions from Hunterdon County Cemeteries, 1910. 54. https://archive.org/details/tombstoneinscrip00deat/page/54

[85] Goodspeed, Marfy. “The Amwell Church of the Brethren – GOODSPEED HISTORIES.” Accessed May 24, 2022. https://goodspeedhistories.com/the-amwell-church-of-the-brethren/

[86] Eisenberg, John Linwood. A History of the Church of the Brethren in Southern District of Pennsylvania. Quincy Orphanage Press, 1941. 412. http://archive.org/details/BrethrenInSouthernPennsylvania

[87] Stryker-Rodda, Kenn. “Part of Our Ancestry in the Stryker Family and Related Branches of the Harshall, Rüdig and Smith Families,” December 1959, 28.

[88] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, July 13, 1990. NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. National Parks Service. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/47df132f-67e7-494a-a0c8-a3a00b5fdab6

[89] Andrea/Andris/Andress

[90] Redicks/Rudig/Reedig/Riddick/Rederick

[91] Yauger/Yawger

[92] Stryker-Rodda, Kenn. “Part of Our Ancestry in the Stryker Family and Related Branches of the Harshall, Rüdig and Smith Families,” December 1959, 28.

[93] “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, July 13, 1990. NPGallery Digital Asset Management System. National Parks Service. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/47df132f-67e7-494a-a0c8-a3a00b5fdab6

[94] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. 2. https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ? (See: Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, Volume 33, pages 20-22ff; Chambers, “Early Germans," pages 498-502; Anthony Harsel, Hunterdon County, Int. Vol. 7, page 102, NJ.)

[95] Pijanowski, Brian. “My Home: 18 Springtown Road, Whitehouse Station, NJ 08889,” 2013. Matthew Smith.

[96] “Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present (Java).” Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm

[97] Stryker-Rodda, Kenn. “John Christian Harshall of Readington.” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey 32, no. 3–4 (October 1957): 49–51.

[98] In Christian’s defense, John and Jacob’s father had died, the sons seemed over their head running the farm, and found themselves embroiled in a legal battle that may have landed them in prison. Had Christian not intervened, but families of these men would have been in dire straits.

[99] Smith, William Francis, and Beverly B. Smith. John Smith, 1718-1791, Descendants. W.F. Smith, 1987. 335. https://www.google.com/books/edition/John_Smith_1718_1791_Descendants/ZVYbAQAAMAAJ?

[100] Ellis, Franklin. History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, New Jersey: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Everts & Peck, 1881. 101. https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Hunterdon_and_Somerset_Counti/AdMwAQAAMAAJ?

[101] Weis, Frederick Lewis, “The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies: New York, New Jersey, And Pennsylvania, 1628-1776,” 1957.243.

[102] Brumbaugh, Martin Grove. A History of the German Baptist Brethren in Europe and America. Brethren publishing house, 1899. 337. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_the_German_Baptist_Brethren/DaroMtJrMpUC?

[103] The Courier-News. “Reunited.” September 16, 1985.